Climate models are unreliable

Home -> Climate models are unreliable

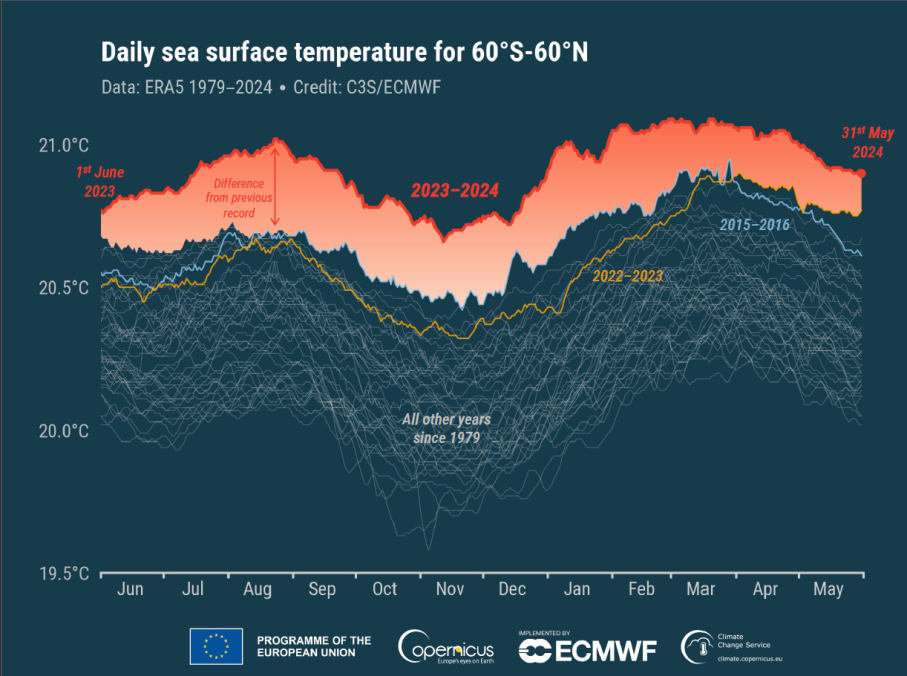

Scientific evidence overwhelmingly supports the reality of climate change. According to the World Meteorological Organization’s 2023 report, 2023 was the warmest year on record, with greenhouse gas levels, sea surface temperatures, and sea level rise at unprecedented heights. The past nine years, from 2015 to 2023, have been the warmest on record. These findings align with NASA’s analysis reporting a significant rise in the average global temperature since 1880, primarily occurring since 1975, at an alarming rate.

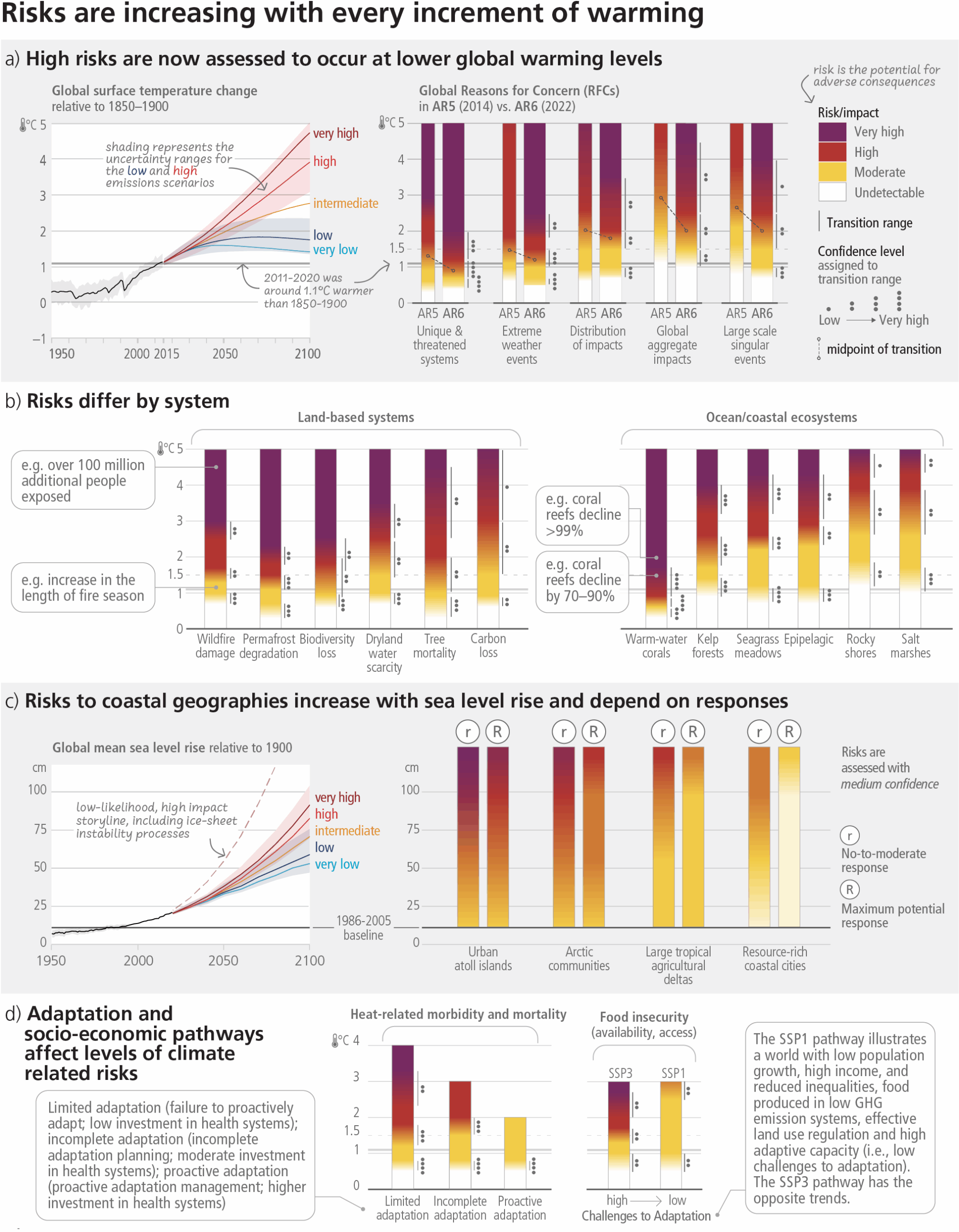

Contrary to the narrative that climate change does not exist, scientific consensus globally confirms that climate change is real and largely caused by human activities. The European Climate Risk Assessment (2023) and the World Economic Forum Global Risk Report (2024) further emphasize the severe impact of human activity, requiring urgent action to mitigate climate change effects. Among the effects that extreme weather is causing are food and water security threats and the impact on ecosystems. Additionally, the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) presents evidence of human-driven global warming, highlighting the pressing need for drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Myth

Climate models are unreliable

Facts

Climate models are not crystal balls. They are physics-based simulations of the Earth system, built around well tested fundamentals such as conservation of energy, fluid dynamics, and radiative transfer. Their purpose is to estimate how the climate responds to changes in “forcings” like greenhouse gases, aerosols, solar variability, and land use, and to do so in a way that can be tested against observations.

A key misunderstanding is mixing up weather forecasting with climate projection. Weather is the chaotic day to day state of the atmosphere, so predicting the exact conditions on a specific date weeks ahead is hard. Climate is the long term statistics of weather, meaning averages, trends, and the probability of extremes. Models can struggle with the exact timing of short term wiggles while still capturing the long term warming trend and its drivers.

Uncertainty does not mean “unreliable.” As in every scientific field, climate research has uncertainties, and they vary by topic, data quality, and methods. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) explicitly communicates certainty using calibrated language, including a five step confidence scale from very low to very high confidence, so readers can see where evidence is strongest and where it is still developing.

When you look across the IPCC’s major conclusions, most of the central findings sit at high to very high confidence. For example, the latest IPCC Synthesis Report (2023) states that climate change is a threat to human well being and planetary health and that the window to secure a liveable and sustainable future is rapidly closing, both assessed with very high confidence. So for the big questions, evidence converges strongly.

Models are also continually tested. One of the clearest checks is hindcasting and retrospective evaluation: run models using past conditions and compare with what actually happened. Peer reviewed evaluations of model projections across decades have found they were generally quite accurate at projecting later global warming, especially once accounting for differences between the emissions assumed in the original scenarios and what occurred in reality.

In 2021, the overwhelming validation and significance of these models led to pioneers getting awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Where, then, do uncertainties matter most? Often they are about the exact size and regional pattern of change, or the timing and magnitude of specific impacts, not about whether greenhouse gas driven warming is real. Aerosols and cloud processes are a classic example: they can widen the range of outcomes because they are harder to measure and represent, but they do not overturn the basic warming effect of rising greenhouse gases. That is why assessments rely on ensembles of many models and many runs to quantify a range rather than a single number.

Newer climate assessments can look more alarming than older ones because evidence is improving and because scientists are better characterizing complex interactions, including the possibility of abrupt changes after warming thresholds in parts of the climate system. Research on climate tipping points and their consequences has expanded substantially in recent years, and IPCC reports discuss that some changes can accelerate once thresholds are crossed, even though the exact likelihoods and timings can still be uncertain.

Taken together: climate models are not perfect, but they are rigorously grounded, continuously tested, and most reliable for the big questions that matter most. They tell us with high confidence that continued emissions raise temperatures and risks, and that uncertainty is largely about how much warming and damage we choose to lock in.

Fact-check by Andronikos Koutroumpelis, FactReview.gr

Sources

- https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

- https://www.carbonbrief.org/qa-how-do-climate-models-work/

- https://science.nasa.gov/earth/climate-change/study-confirms-climate-models-are-getting-future-warming-projections-right/

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2021/summary/

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/how-climate-models-got-so-accurate-they-earned-a-nobel-prize